Restoring a Disappearing Lakeby Georgann Penson |

||

When Lake Jackson "disappeared," governmental agencies jumped in. The Northwest Florida Water Management District, along with state and local governments, were prepared to implement a massive clean-up plan to restore the lake to its previous ecological health and to its renown trophy largemouth bass days. Lake Jackson, a popular 4,000-acre lake located north of Tallahassee, Florida, in Leon County is geologically unique. The dissolution of limestone in years past caused overlying sediments to collapse and form a solution basin, creating the lake. Two active sinkholes in the bottom of the lake are remanent features of these karst processes - Lime Sink in the northern portion and Porter Hole Sink in the southern area. The lake is in a closed 27,000-acre drainage basin. Water flows into the lake but water can only leave through evaporation or leakage through sinkholes in the bottom of the lake. A number of other lakes in the region share this characteristic, although each lake has a unique, natural cycle.

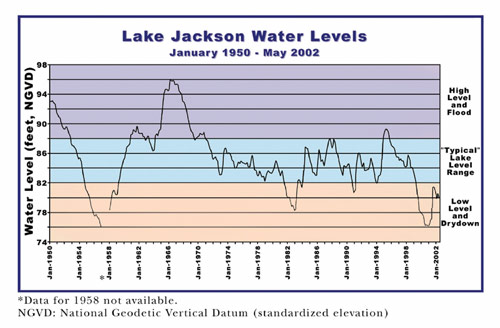

When a combination of factors are present - below normal rainfall, low lake levels, below normal ground water levels and high rates of evaporation - water flowing into the sinkholes becomes more obvious. In the last stages, the lake has the appearance of draining rapidly as though someone pulled a plug from a bathtub, although in reality it has been draining slowly over time. On September 16, 1999, most of the water remaining in the southern portion of Lake Jackson drained through Porter Hole Sink, an eight-foot wide sinkhole, leaving only isolated pools. The largest pool in the northwest portion of the lake drained slowly into Lime Sink over the next six months and in May 2000, this portion of the lake was completely dry. The first documented disappearance of the lake's water was in May of 1907. The lake also disappeared in 1909, 1932, 1935, 1936, 1957 and 1982. Today, water managers call this process a natural drawdown, dewatering, draining or drydown. The Impacts of Development Planning for Restoration The Northwest Florida Water Management District, in cooperation with other state agencies and local governmental entities, had already developed a Lake Jackson Management Plan through the state's Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM) program. This comprehensive management strategy recommended development of a contingency plan for removing years of accumulated muck on the bottom of Lake Jackson should the lake experience a natural drydown. "Contingency plans are not glamorous and it is difficult to sustain interest in developing such plans," said Tyler Macmillan, SWIM coordinator for Lake Jackson. "You don't know if you will ever get to implement it." "However, having a formal, approved watershed management plan allows those involved to agree upon the basic concepts and work toward development of specific action plans," he explained. "This is good watershed planning because it allows the problem to be identified and enables you to obtain a high level of agreement on the solution. This was particularly important with the drydown restoration project because delays might lessen the project's success." As the lake level declined in the spring of 1999, Macmillan convened a multi-agency technical working group to plan the restoration effort if, and when, the lake were to drydown. This group later became known as the Drawdown Interagency Restoration Team (DIRT). Strong citizen support and participation also were encouraged. The "teamwork" of this group has been credited with the project's high level of success. Macmillan acknowledges that his interest in Lake Jackson stems from his earlier, personal experiences. A long-time resident of Tallahassee, he grew up fishing in the lake. He vividly recalls, as a teenager, driving his truck on the exposed lake bottom in 1982 when it last drained, occasionally getting stuck in the muck. Undertaking needed research, such as laboratory analyses of the sediment, was the first step in implementing the project. Other steps included developing specific engineering plans, identifying phased activities or specific actions to take place when the water level dropped to a particular level and obtaining necessary permits. "Identifying the triggers, recognizing when they are there and then gearing up quickly to begin the restoration effort was crucial to the success of the project," explained Macmillan. "An action plan was developed that clearly established the priorities and critical tasks." When it became evident that the lake was likely to drain, time became a crucial factor in implementing the restoration project. An ongoing threat was that the lake would refill before there was time to secure local, state and federal environmental permits and mobilize contractors. In 1982, the lake refilled in about four months. How much time would be available to remove the muck could not be predicted. - story continued below.

The Project Phase I of the project was completed before any major rainfall events, but work was temporarily interrupted during Phase II when tropical storm Helene deposited approximately eight inches of rain on September 22, 2000, flooding the southern portion. Hurricane Gordon, after being degraded to a tropical storm, had already dropped one inch of rain on September 17. Portions of the lake had to be dewatered with pumps to allow the completion of work underway. The Leon County Public Works Department oversaw the contractors performing most of the work although the Fords Arm portion of Phase I was handled by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The contracts were structured so work could be done incrementally as funding and other circumstances allowed. The bidding and construction management elements were somewhat unusual. Bidding was done on a unit cost (per cubic yard) basis only with no allowances for mobilization, demobilization or other ancillary costs. "Uncertainty about the working conditions in the lakebed and the unit cost probably resulted in higher bids initially," explained Macmillan, "because the contractors were taking a great deal of risk. For example, if three truck loads of muck were removed and then the project was completely rained out, the contractors would be paid for three truck loads only." Macmillan reflected that, overall, this approach ensured the wise expenditure of public funds. "The bidding and construction management phase was a little awkward, but a learning experience," he said. Earthmoving equipment was used to remove and load the sediment into dump trucks, which hauled the material to approved disposal sites. One of the first major obstacles to overcome was the identification of appropriate disposal sites. Over 100,000 dump truck loads of muck were removed from the lake. Sediment was deposited on contained upland sites and in the contractors' private borrow pits but most went to nearby private property. Removal costs ranged from $1.20 to $8.00 per cubic yard, with the average over the entire project being about $4.00 per cubic yard. Funding for the project was obtained incrementally, eventually exceeding $8.2 million, and came from a number of contributors: Leon County, Florida Legislature, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the Northwest Florida Water Management District. An estimated additional half million dollars of in-kind services were provided for planning and implementation of the project.

When Life Gives You Lemons - Make Lemonade

This natural draining allowed the easier removal of an invasive exotic tree, the Chinese tallow, from the shores of Lake Jackson. Prescribed fire was undertaken on the lakebed to reduce biomass and improve habitat. Public boat landings and private docks were improved and repaired. Hundreds of area residents participated in several public trash pick-up events to remove litter from the lakebed and shoreline. Several boat motors, shoes, batteries, sunglasses, folding chairs and a boom box were recovered. Over three hundred area residents participated in a 5k run on the dry lakebed. Area residents biked, hiked or jogged on the dry lake bottom. Birding, hunting and horse-back riding were other recreational options. Traditional fishing gave way to "unique fishing" such as capturing or catching the fish stranded in some of the pools of water. When the lake was in the final stages of draining, fish were actually caught with bare hands as they were forced to congregate in small, shallow pools of water. More typical amounts of rain have fallen during 2002 and the lake is slowly beginning to refill. Refilling of the lake generally occurs when regular, wet weather patterns return and inflows to the lake exceed the draining capabilities of the sinks. In 1957, attempts were made to plug Lime Sink by dumping materials such as soil, wrecked automobiles, concrete blocks and truckloads of cement into the sinkhole opening. Today, lake managers believe the natural way is best. L&W For more information contact Georgann Penson or Tyler Macmillan, Northwest Florida Water Management Water Management District, 81 Water Management Drive, Havana, Florida, 32333-4712; (850) 539-5999. |

©2002, 2001, 2000, 1999, 1998 Land and Water, Inc.